Not that that has any real bearing on the topics for today, which are the ethics and issues (and economics) behind a tournament organizer (specifically, someone who’s on the hook for any overlay) participating in the tournament.

Several weeks back, a thread popped up on 2+2, claiming that the sponsor of a small tournament series had offered to refund half the buy-in to players, in exchange for half of any profit in the tournament. The tournament had a guaranteed prize pool, not enough players had entered the tournament to fund the prize pool with entry fees, so the sponsor of the tournament would be forced to pay any portion of the guarantee not matched by player fees, something that is known as an overlay.

For the purposes of this discussion, let’s assume all of these things are true: 1) The guarantee was unmet by player contributions. 2) The sponsor was committed to honoring the guarantee. 3) The sponsor was actually offering to buy half the profit from players. Is this a good idea?

Balance of Terror

Conventional wisdom would say there’s no way for the sponsor to lose money with this plan. Some of his players win some money, he doesn’t pay them as much (because he’s bought half their action), and he offsets a portion of the overlay. In reality, things can get messy.

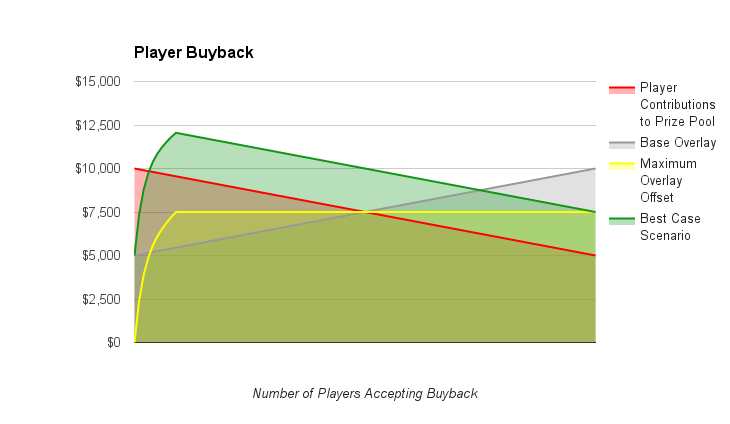

For simplicity’s sake, let’s say the tournament has a $15K guarantee. It gets 100 entries at $100 each, with only $10K contributed to the prize pool. With 100 entries, the top 9 players will win all the money. In this scenario, the sponsor is out $5K in overlay.

If the sponsor can get the 9 players who win all the money to agree to his terms (and nobody else), he will have refunded $450 in player fees, making the amount players contribute to the prize pool only $9,550. But he only has to pay $7.5K in prize money, so he’s actually ahead by $2K!

On the other hand, if 9 players who don’t cash take the deal, the sponsor not only still has to pay out the original overlay but is also out the $450 in player fees that have been refunded.

If he can get everyone to agree to the split? He only pays out $7.5K–half the guaranteed prize pool–but everyone’s only paying $50 per entry, and with just $5K contributed by players, the overlay is still $2.5K.

There’s obviously some potential for mitigating losses with this strategy, but as the sponsor, if you whiff on picking winning players, you’re actually out even more money than the initial overlay.

Opinions on the sponsor’s action varied, with some claiming that it would be irresponsible for him not to try to offset his losses, and others decrying it for creating the impression the “house” was trying to cheat the players out of the prize pool. On this, I have to come down in the middle, since the more action the sponsor buys up, the more money they stand to lose, unless they pick the right people. It’s a gamble, just like any other situation where someone backs several players in the same tournament.

Amok Time

There’s a similar but distinct situation that is far more problematic, which I’ve seen happen in a variety of venues. In a tournament with an overlay and multiple re-entries allowed, the sponsor uses the overlay to put in one or more players who can play a high-variance style, with the intent of building up a big chip stack, knocking out non-sponsored players, and the ability to re-enter at no cost to either the player or the sponsor. In our example tournament above, the $5K overlay represents 50 buy-ins. With low registration early in the tournament and a large expected overlay, a sponsor could make a deal with several players to take more risks, with the promise that they’ll be bought back in by the sponsor several times, if need be.

So long as the number of entries and re-entries by both non-sponsored and sponsored players doesn’t exceed the guarantee, the sponsor isn’t taking on any extra risk. But they’re essentially playing against the people who have put up money to play in the tournament, and one of the things that has distinguished poker from casino table games has always been that you’re playing against other players, not the house. The sponsor of a guaranteed tournament is assuming risk when they announce the guarantee. They expect to make their costs back through entry fees and other spending by the players. But if it looks like their bet isn’t going to pay off, putting a thumb on the scale by using house money against the players they’ve brought in with the promised guarantee smacks of unethical practice.